Gustave Courbet, “The Painter’s Studio: A Real Allegory Summing Up Seven Years of My Life as an Artist”, 1854 – 55, oil on canvas, 142 × 235 inches Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

NOTE: This post was prepared and edited from a monograph I wrote more than 35 years ago. -P

Unlike previous eras, the materials and tools of today’s artists are widely and easily available. In comparison to the hundreds of years before “modern painting”, it seems that technical excellence was in decline and artists were circumventing or ignoring traditional and long-proven techniques – a misguided approach.

Experimental and uninformed use of varnishes and materials inevitably led to surface anomalies and color changes then, as they still do today. The lack of sophistication in the preparation and handling of artists materials coincided with the changing role of the artist in society. Although right into the 18th century painting was still regarded as a trade, artists were now seeking acceptance of their “creativity” in addition to their craft. This process of intellectualizing art offered an acceptable route to higher status for the aspiring painter and it was during this time in England that the Copyright Act of 1735 was enacted. William Hogarth, known as the “father of modern British satire” because of his innovative social and political satirical engraving, was a pioneer in copyright for artists as well. His work was so heavily plagiarized that he lobbied for the legal protection of engravings. As a result, the Copyright Act passed by Parliament in 1735 is also known as the Hogarth Act, acknowledging intellectual content and making a distinction between artists and mere craftsmen. Although these were major events in the recognition of the artist in society, there was a downside. This new scholarly approach to painting eventually led to the demise of the studio or workshop tradition – “making art” could no longer be considered a trade. With the rise of the middle class in the 17th and 18th century, along with the climax of industrialization in the 19th century, artists and their art were able to reach vast new markets.

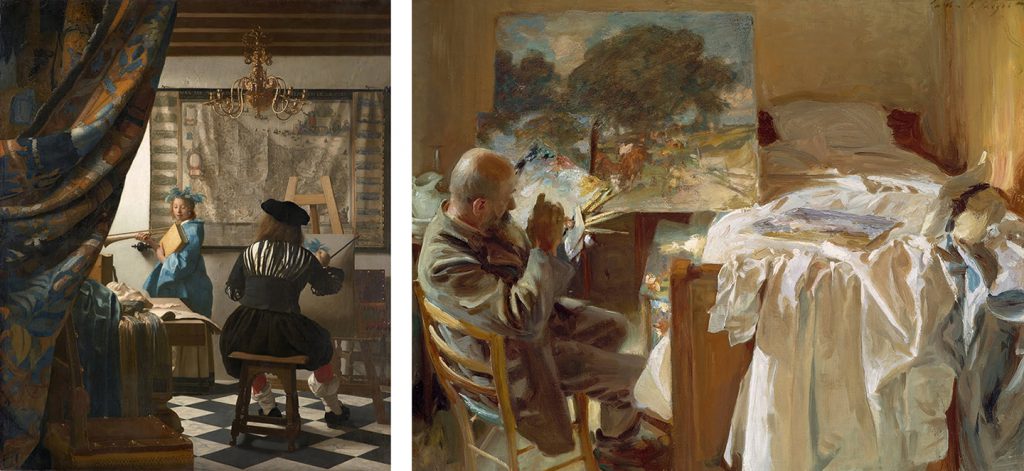

left: Johannes Vermeer “The Art of Painting”, also known as “The Allegory of Painting”, or “Painter in his Studio”, 1668, oil on canvas, 105 x 87 inches, Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien. right: John Singer Sargeant “An Artist in His Studio”,1904. oil on canvas 22 1/8 x 28 3/8 inches, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts.

left: Robert Hubert “Artist’s Studio” 1760, Städel Museum, Frankfurt, oil on canvas, 22.25 x 28.5 inches. Hubert, 1733 –1808) was a French painter in the school of Romanticism, noted especially for his landscape paintings and capricci, or semi-fictitious picturesque depictions of ruins in Italy and of France.This painting probably dates from Robert’s period of study in Rome, for while it is artistically ambitious there are flaws in the perspective. It is perhaps no accident that he has depicted an artist working on a relief: Robert, who was to become such an important painter of architecture and townscapes, had learned drawing from a Parisian sculptor. right: Pablo Picasso “The Painter in his Studio” “(Le Peintre Dans Son Atelier)”, 1963, oil on canvas 23.4 × 36 inches, Yale University Art Gallery.

This, unfortunately did nothing to increase the quality of art. As long as art could be supplied in mass quantity, the masses would pay for decoration, however bland, just like today. In reaction, over time, an elite group of artists and dealers developed, creating and encouraging an awareness of art as separate and distinct from the vulgar concerns of the mass marketplace. To create and appreciate art, it had to be seen as distinct from the mere ability to purchase it. The modest practicalities of the painting trade were slowly disappearing and being replaced with “originality” and “creativity”– seen as the new the hallmarks of true talent. In the process the artist lost touch with his own support system of artistic production, thereby increasing his isolation. Important practical skills – the artist’s heritage – gave way as the new “art” dealers continued to declare the “new creativity,” and its often less than profound theories and concepts as the reason for which a painting – or any art – was of value.

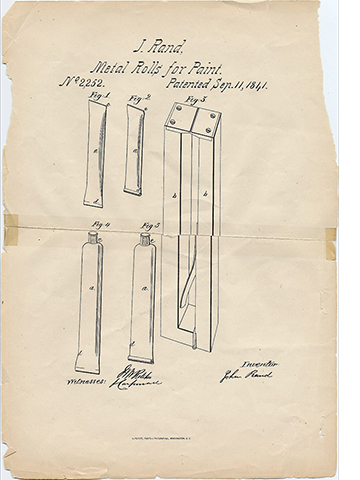

With artists achieving some form of success through their daily activities, painting could now be considered a pastime activity or “hobby.” Encouraged by the invention of the lead paint tube in 1841 by the American artist John Goffe Rand, painters became mobile, leaving the comfort of their studios to paint in the field – thus was the beginning of Impressionism and the transition, via Paul Cezanne, to Modern Art. This also allowed a growing group of “amateur” painters easy access to materials once reserved for the few.

left: John Goffe Rand, Drawings for his collapsible metal tube for paint. United States Patent Number 2,252. Published by the United States Patent Office. “Improvement in the Construction of Vessels or Apparatus for Preserving Paint” © September 11, 1841, size 11.5 x 7.875 inches. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Goffe Rand patented his creation in 1841. Until that year, if a painter took his materials to paint outdoors, he had to carry his pigments in pig bladders. The ability to preserve paint in collapsible tubes, which kept the colors usable until they were finished, was a stimulus for artists such as Camille Pissarro, considered a father-figure to many in the impressionist movement, Claude Monet and Paul Cézanne – who provided a legacy for a revolution of form that paved the way for modern art – to get outside the confines of the studio and paint.

An extreme example of what can can happen when artists use materials that might be appealing but untrustworthy would be Mark Rothko’s large mural series, executed in a palette of deep reds, blacks, and maroons, were painted in 1962 and acquired for Harvard University in 1963. Rothko admired the penthouse dining room intended for ceremonial functions with their sunny, scenic views of Cambridge. When he donated the works to Harvard in 1963, he stipulated in his deed of gift that they be shown only there. However, in less than 30 years time the murals had begun degrading. Exposure to high levels of light led to dramatic fading, and they were removed from display in 1979. The fading of these murals has been attributed to Rothko’s choice of the highly fugitive pigment, Lithol Red.

top: Mark Rothko’s original artwork as it appears today. bottom: The technological restoration. A new presentation of Rothko’s Harvard Murals features innovative, noninvasive digital projection as a conservation approach. The exhibition returns this mural series to public view and scholarship while also encouraging study and debate of the technology. The technique employs a camera-projector system that includes custom-made software developed and applied by a team of art historians, conservation scientists, conservators, and scientists at the Harvard Art Museums and the MIT Media Lab. The digital projection technology restores the appearance of the murals’ original rich colors, which had faded while on display in the 1960s and ’70s in a penthouse dining room of Harvard University’s Holyoke Center (now the Richard A. and Susan F. Smith Campus Center), the space for which they were commissioned. Deemed unsuitable for exhibition, the murals entered storage in 1979 and since then have rarely been seen by the public. Each day at 4pm, the projectors are turned off to provide visitors an opportunity to see the murals without projected light.

When conservators studied the Harvard murals and analyzed the materials used in their creation, they discovered that the main cause of the color alteration was the light sensitivity of the pigment Lithol Red. Lithol red (PR 49) is most commonly associated with the printing industry, where it has been, and still is, used for low-cost printing inks. Rothko used this pigment extensively, especially in the plum-colored background of the murals, but he had little way of knowing that while it is stable as a powder, Lithol Red becomes highly susceptible to fading when combined with a binding medium such as the animal glue and egg that the artist preferred. Such light damage is irreversible – Lithol Red’s major drawback is its poor lightfastness – a fault that has serious implications if it is used for artistic purposes

What happened to Rothko’s murals delivers a powerful lesson to artists ill-trained in materials and to uninformed owners of 20th-century paintings. Whatever combination of natural and man-made events conspired to bring about the special problems Rothko’s murals suffered, these paintings ultimately serve as poignant reminders of art’s particular vulnerability.

British landscape painter Joseph Mallord William Turner also did not make savvy choices of his paints, and was notoriously indifferent to the permanence of his palette colors. He just did not care. In a famous exchange between Turner and William Winsor, of Winsor & Newton, on the topic of color permanence of the pigments he was buying, Turner is said to have told Mr. Winsor to mind his own business. Before the introduction of reliable synthetic paint colors, some paints were much more durable than others. A questionable choice could make one or more of your colors disappear quickly by reacting with air and light, or it might interact with an ingredient in a nearby paint, binder, or varnish and turn into an unintended color. It was important to choose reliable and lasting pigments, but Turner often didn’t. As a result, his works often faded very quickly – sometimes within just a few years. While his paintings seem by all appearances to still be in great shape, many of them used to be much brighter and more vibrant in a way we can only imagine today.

Considering the limited materials available to the artists of centuries past, the modern painter’s accomplishments seem trivial. Additionally, artists are no longer an important market for today’s colorman. In fact, less than 10% of all pigment used today is destined for fine art. The remaining 90% is relegated to various chemical and industrial concerns, primarily the printing industry, where permanence is not an overriding concern, and the automobile industry where pigments need to last only 10 or 20 years in direct sunlight. Nearly all the major manufacturers of artists pigments are giant corporations or a subsidiary of unrelated industries. They need to answer to their Board of Directors and shareholders who know that school, hobby, and crafts represent a larger market share than fine art, and are thus more profitable. Since most artists do not pay attention to these invisible trends, the manufacturers can continue to sell and introduce paints with meaningless exotic or romantic names in order to increase sales.

Unknowledgeable and unskilled, with time on their hands thanks to the modern miracles of industrialization, combined with a growing emphasis on creativity and originality, now anybody could paint. The line between professional painter and talented amateur increasingly blurred to the point where the categories became meaningless. Thus began a trend in which many untrained painters have become recognized as major artists. Since the late 1950s or so, it almost seems that to have knowledge of or embrace any of the practicalities of the artists craft is a liability. With the overriding preoccupation of “originality,” a visit to just about any gallery in any city in the United States or abroad, or a glance through just about any art magazine or popular publication featuring “art content”, derivative, mediocre (at best), and perfunctory works abound, showing that a lack of training and denial of tradition often seem to be a distinct advantage to an aspiring artist.